by Annetta Kapon

BOMB 125/Fall 2013, ARTISTS ON ARTISTS

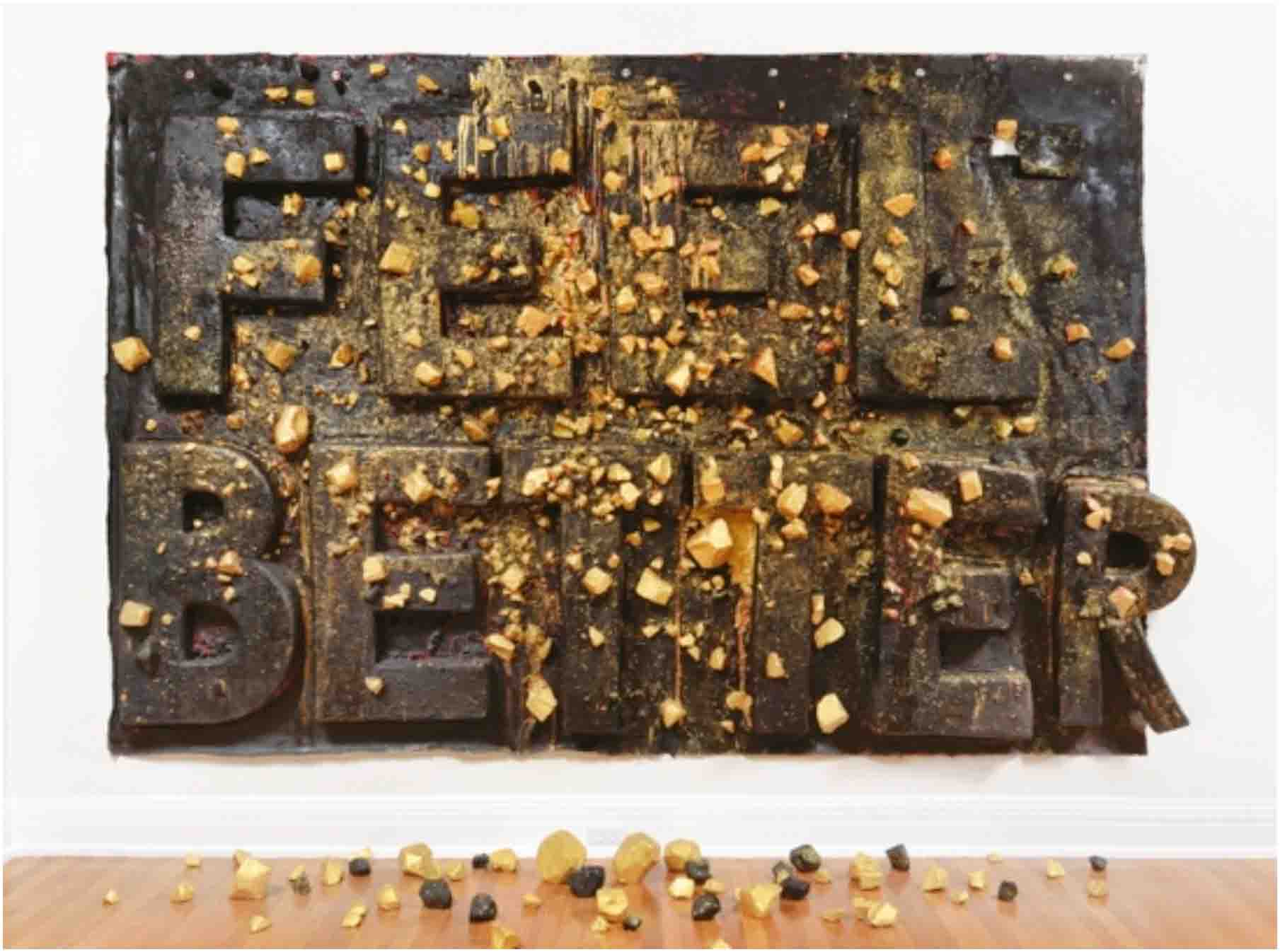

FEEL BETTER, 2012, acrylic and oil paint, high-density and upholstery foam on canvas, 93×132 x 8 inches. Images courtesy of Luis De Jesus, Los Angeles.

FEEL BETTER: The exhortation, wish, or command, chiseled in “stone” calls to me in huge upholstered capital letters from what looks like a black vertical gravestone in relief hung as a tapestry on the wall. On it and on the floor are shiny gold-colored nuggets or “rocks.”

Miyoshi Barosh’s 2012 installation concentrates in one piece her deft use of linguistic slippage, and the dark humor of double entendre. Through the intense materiality of language-as-sculpture, the work activates a kind of monumental craftsmanship that oscillates between the fleeting virtuality of a Facebook “wall” and the timeless finality of a tombstone. That the work is made of illusionistic movie prop materials (fabric, paint, foam, fake gold) adds to this collision.

The clash produces in the viewer a Brechtian estrangement effect, as when we are obliged to stand at a certain distance from the work, a distance that prevents us from being sucked in by the face value of language or the seduction of workmanship in the materials alone. According to the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, “words are deeds.” Language is material; speech is not the opposite of action. Feel Better orders us to feel better (or else?); personal feeling becomes enforced as a marketable social product.

Labor also plays a big role in Barosh’s work—namely as the language of labor, and the labor of language. What appears as Pop craft such as knitting, sewing, or patchwork, is a gendered way for Barosh to engage in the labor that capitalist industry and high technology have supposedly liberated us from.

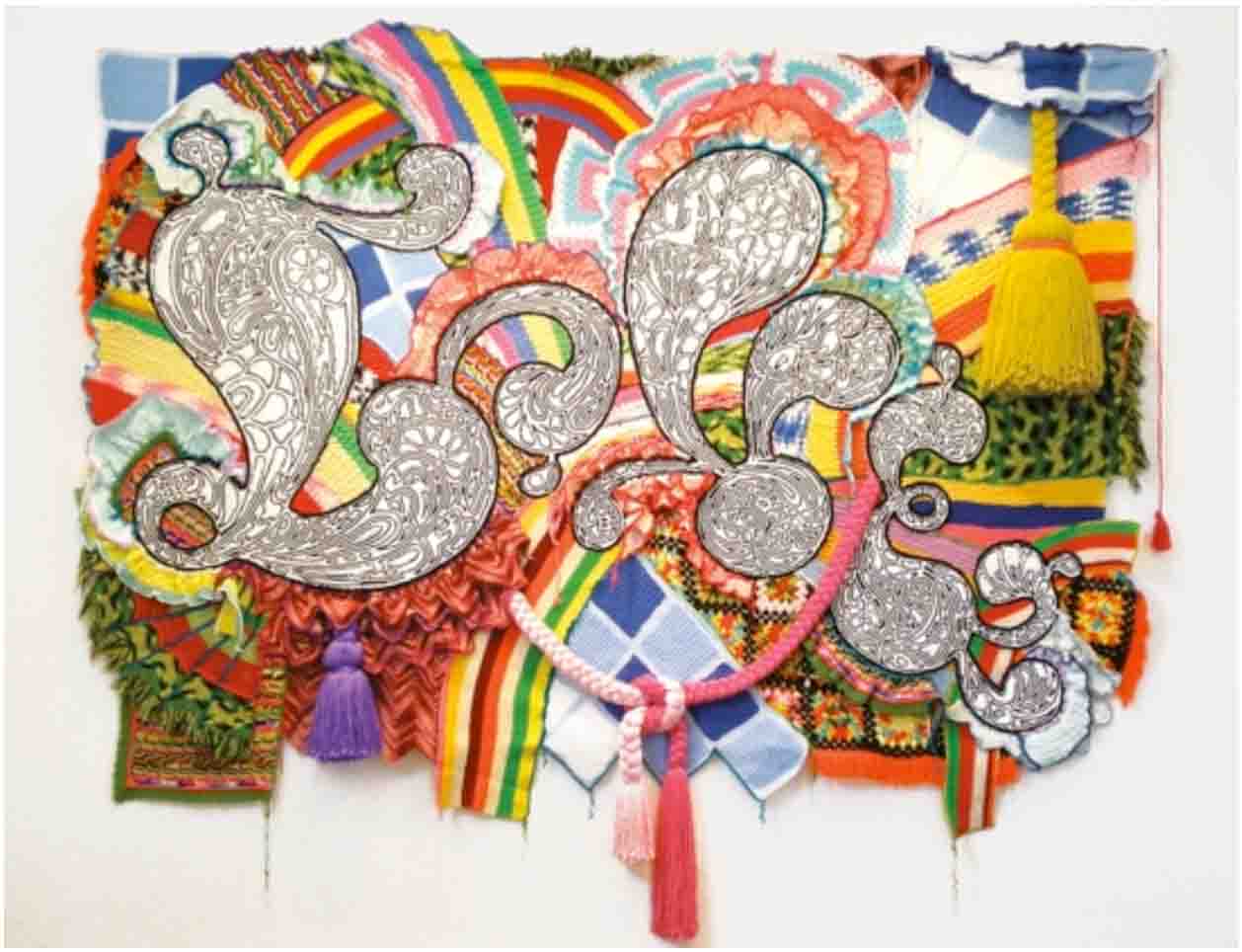

Love, 2007, found afghans, acrylic yarn, and pom-poms on canvas, 96×114 x 10 inches.

Love, 2007, found afghans, acrylic yarn, and pom-poms on canvas, 96×114 x 10 inches.The meaning of the artwork results neither from the straightforward declarative function of a linguistic message, nor from the materials or technique: In Love (2007), the speech action is situated within an orgy of garish afghans, embroideries, and knitting. At once triumphant, pathetic, and humble, Love carries within it primarily the collision and collusion between form and content but also the contradictory messages of a number of discourses, from the cheerful psychedelic designs of the ‘60s, to the invisible, devalued, and discarded labor of other women (euphemistically renamed “labor of love.”)

If we think of J. L. Austin’s and John Searle’s concepts of Speech Act Theory, what we have in front of us is the productive friction of declarative, directive, and expressive meaning: language is always in danger of being swallowed up by the context, and the medium is always resisting the tyranny of the message.

— Annetta Kapon lives and works in Los Angeles producing video, sculpture, and installations. She teaches in the Graduate Fine Arts department at Otis College of Art and Design.